Every change of context, every change of medium can be interpreted as a negation of the status of a copy as a copy—as an essential rupture, as a new start that opens a new future. In this sense, a copy is never really a copy; rather a new original in a new context. Every copy is by itself a flâneur—experiencing time and again its own “profane illuminations” that turn it into an original. It loses old auras and gains new auras. It remains perhaps the same copy, but it becomes different originals.

Boris Groys, Going Public

Flâneurs in the collection of the Centre national des arts plastiques

Flâneurs is a curatorial project on paper that results from an exploration of the collection of the Centre national des arts plastiques (CNAP), Paris, I have carried out in 2015-2016 as part of a curatorial research grant. This programme offers independent curators and art critics the opportunity to test out innovative and alternative research methodologies using the CNAP’s collection and archives. This unique and plethoric collection was initiated in 1791, just after the French Revolution, when a dedicated budget was set aside for the State to support living artists by purchasing or commissioning original works or copies. The mission of encouraging emerging practitioners through support programmes and acquisition of artworks persists today. The CNAP’s collection is a collection without walls – since its foundation, works are loaned and displayed in national museums or to State and local government administrations in France and abroad.

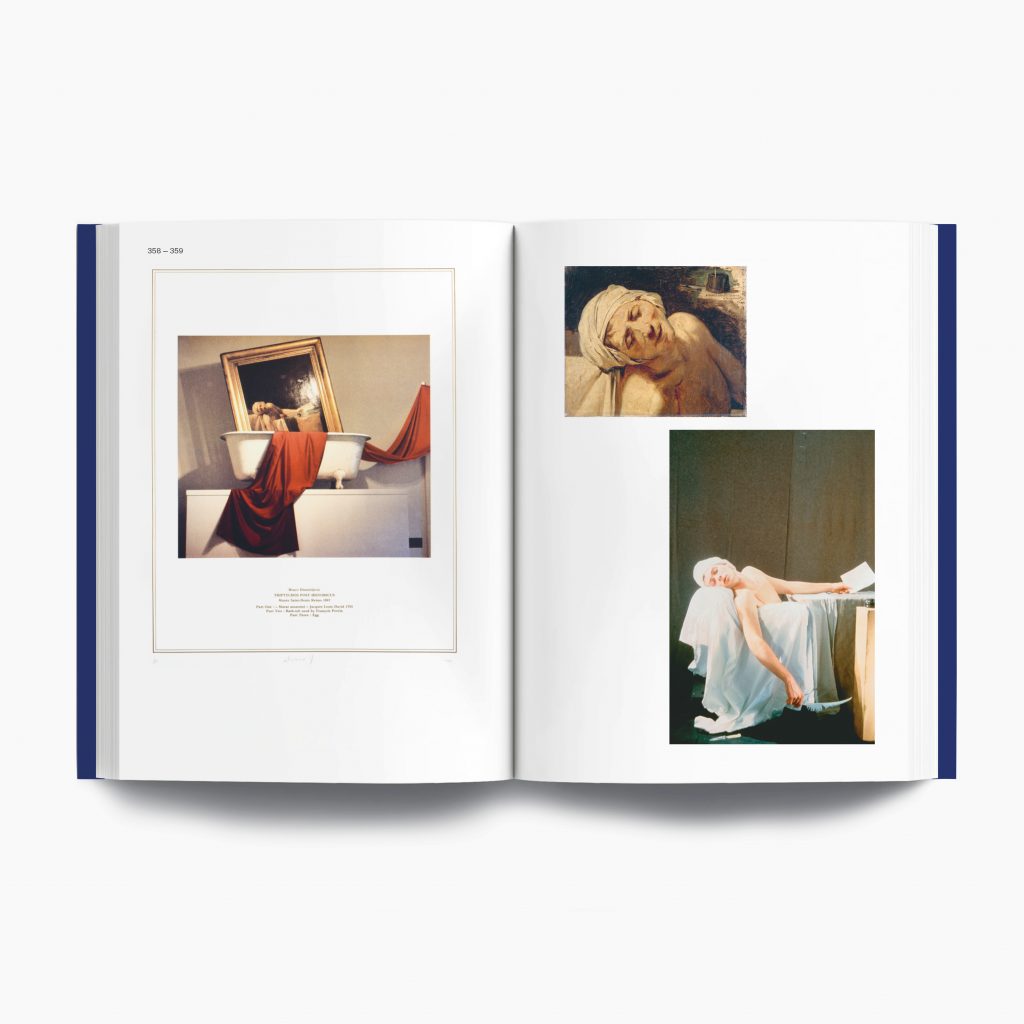

My research at the CNAP developed around the question of reproduction of artworks and relied on two large bodies of work: nineteenth-century’s copies and casts, and contemporary works that reappropriate or quote images that have entered collective memory through their massive dissemination within the consumer society. Taking on an iconological point of view, I wanted to show how reproductions of artworks can be considered as expressions of a specific historic, cultural, and socio-political context, in the same way as originals. Therefore, in the project, copies and contemporary artworks acquire the same status and are treated on the same level to highlight how contexts of production and dissemination of artworks’ reproductions have changed over time.

Braco Dimitrijević, Tryptychos Post Historicus, 1989. Lithograph, FNAC 89261 (89). Paul Baudry, Marat dans sa baignoire, 1861. Copy after Jacques-Louis David. Oil on canvas, FNAC PFH-4051. Philippe Jacq, Sans titre, Jack Andko Production, May 2001. Color slide, FNAC 01-221

Radical museology, or art at the end of art history

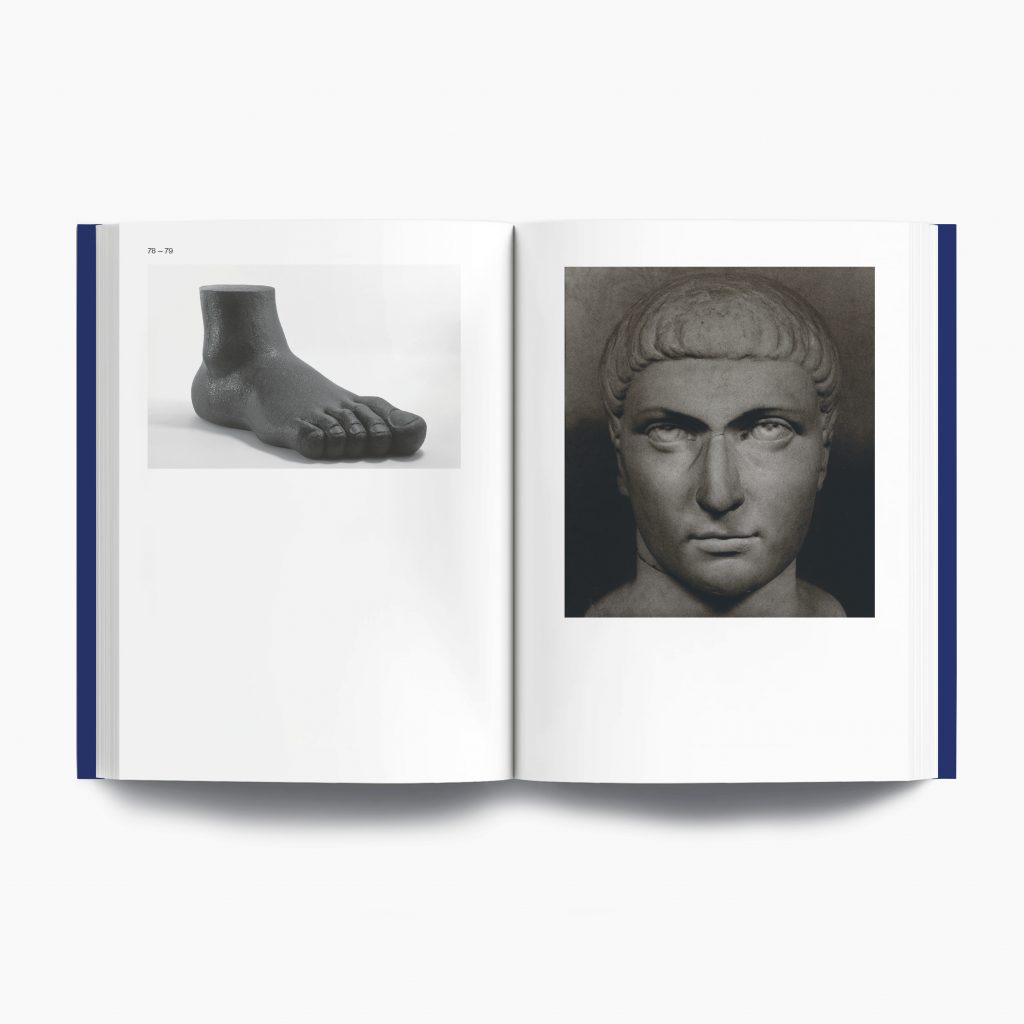

As stated, Flâneurs is a curatorial project on paper. The format of the book has allowed me to articulate an alternative narration developing from over three-hundred works of the collection located in storage, museums, national and local administrative offices, and art schools throughout France. Flâneurs is structured as a curator’s tour in an imaginary museum – the reader is guided through the ‘galleries’ by an interview between Juliette Pollet, curator in charge of the CNAP’s Visual Arts Collection (from 1990 to the present), and myself. The ‘galleries’ are organised around a classical museography, from the Antiquities to today. This structure allows an anachronistic visual narration to unfold, which is inspired by artistic perspectives inaugurated by ‘art after the end of art’ (Belting 1983, Danto 1998) and recent innovation in museum displays that Claire Bishop (2013) has defined as ‘radical museology’. Photographic reproduction has allowed me to create ‘fictional collisions’ that have revealed new relationships between historical works and contemporary objects in the CNAP’s collection.

The interview between Juliette Pollet and myself brings to the fore a strong subjective viewpoint that has permeated the research, which also allows the emerging of a constellation of meanings through facsimiles of historic documents, a great number of quotations, and interviews with artists Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Aurélien Mole, and Matthew Darbyshire. The artists’ voices reveal alternative interpretations and uses of reproduction and appropriation in contemporary art.

Museums without walls

To punctuate the ‘evolutionary’, museographic, structure of Flâneurs are two focuses on professional copyists and imaginary museums. The first focus reveals the importance of copyists in nineteenth-century France, notably during the Second Empire (1852-1870) when the number of commissioned copies of religious paintings in the collections of the Louvre – besides official portraits of Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie – excelled the acquisitions of originals. This chapter also draws on Paul Duro’s research (1986, 1988) and looks at the sociology of professional copyists to highlight the reasons why many women artists undertook this job. As they reached a peak during the Second Empire, painted copies in France continued to be commissioned throughout the Third Republic and until the 1910-20s.

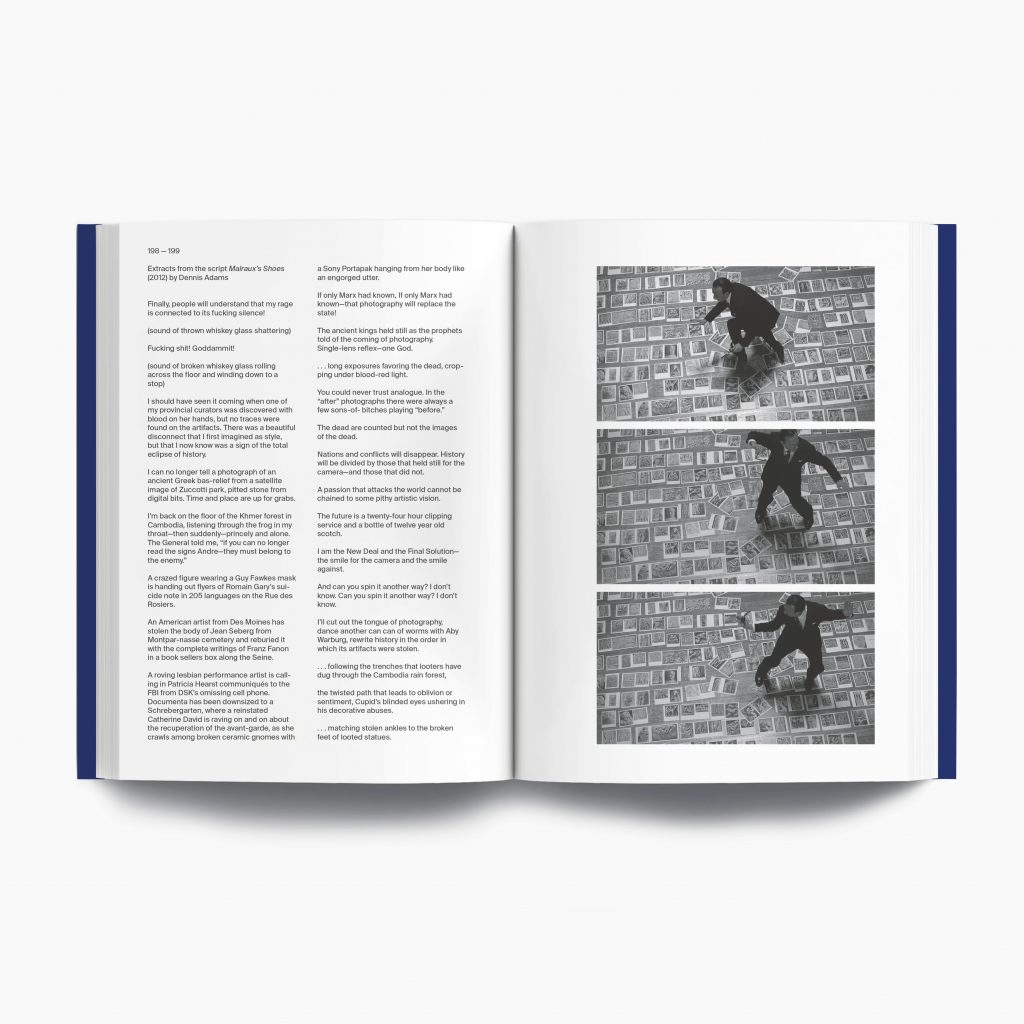

The focus on imaginary museums is a direct nod to André Malraux’s famous essay Museum without walls (1953), in which he stresses the importance of photography in art-historical studies and in revealing stylistic similarities in fine and applied arts. A reference point for several artists in the collection, it has notably inspired the conception of a project by sculptor Pierre Székely, who aimed, in the late 1960s, to open in Paris a ‘built imaginary museum’ that would gather slides of masterpieces from all over the world, to be used for individual research or for public happenings. Dennis Adams’s film Malraux’s Shoes (2012) directly references a series of photographs showing Malraux in his office choosing the plates for his upcoming book The Voices of Silence (which also gathers the essay Museum without Walls). Furthermore, this chapter shows the historic preliminary to Malraux’s imaginary museum, the Musée Européen des Copies, which was open for a very short time at the end of the nineteenth century in Paris, and of which the CNAP has inherited some of the copies.

Needless to say, Malraux’s imaginary museum has influenced the development of Flâneurs since the first stages of my research in the CNAP’s collection, and has also determined the editorial choice to transform the scale of the images in the book in relation to the original:

In an album or art book the illustrations tend to be of much the same size. Thus works of art lose their relative proportions; a miniature bulks as large as a full-size picture, a tapestry or a stained-glass window. The art of the Steppes was a highly specialized art; yet, if a bronze or gold plaque from the Steppes be shown above a Romanesque bas-relief, in the same format, it becomes a bas-relief. In this way reproduction frees a style from the limitations in which made it appear to be a minor art.

(Malraux 1974, 21-22)

Francesca Zappia | Independent curator and researcher | website: Francesca Zappia | email: francesca.zappia(a)past-forward.net

Order her new book Flâneurs direct from the publishers here.

Select bibliography

Belting H. (1987) The End of the History of Art? [1983]. Translated by Wood C. S. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bishop C. (2013) Radical Museology or, What’s ‘Contemporary’ in Museums of Contemporary Art?. London: Koenig Books.

Danto A. C. (1998) After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Duro P. (1986) “The ‘Demoiselles à Copier’ in the Second Empire,” Woman’s Art Journal 7.

Duro P. (1988) ‘Copyists in the Louvre in the Middle Decades of the Nineteenth Century’ Gazette des Beaux-Arts 111.

Malraux A. (1974) ‘Museum without Walls’, Voices of Silence [1953]. Translated by Gilbert S. Frogmore, UK: Paladin.

Panofsky E. (1955) ‘The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline’ [1938], Meaning in the Visual Arts. New York: Doubleday.

***

Zappia F. (2021) Les Flâneuses. Copies, appropriations, citations dans la collection du Centre national des arts plastiques. Paris : Cnap & Shelter Press.

Zappia F. (2022) Flâneurs. Copies, appropriations, citations from the collection of the Centre national des arts plastiques. Translated by Valinsky R. Paris: Cnap & Shelter Press.

All images courtesy CNAP & Shelter Press.