Principles and guidance for museums and heritage

Our key resource, first published in July 2020, is an illustrated 20-page leaflet, New Futures for Replicas: Principles and Guidance for Museums and Heritage. Read and/or download it as a low-resolution pdf here.

Contact us to request a high-resolution pdf, for best quality printed copy, in page or spread format.

We promote the following principles:

(A) New understandings of authenticity recognise replicas as original objects in their own right with stories worth telling

- Replicas, like all objects, have their own biographies and life stories, and those life stories will necessarily diverge from their historic originals.

- New approaches to authenticity recognise that authenticity is not an intrinsic, material quality of a thing, but a socially mediated experience.

- The materiality, location, use, accessibility, social context, biography, technology / craft of production and authorship will inform how authenticity is experienced and negotiated.

- The production of replicas, including the practitioners involved and the technical and craft practices deployed, is important and often under-researched.

- Co-producing replicas, not least with local communities, can stimulate interest, debate and wider democratisation of heritage and museum practices through the co-production of meaning and establishment of authenticity, values and significance. The benefits of such activities may lie in the process rather than the end-product.

(B) Replicas are distinctive as ‘extended objects’ with ‘composite biographies’ that link the lives of the copies and original

- ‘Relatedness’ is a fundamental characteristic of replicas, because their meaning and value is in large measure a product of their relationships with people, places and other things, which may include further replicas. Appreciating the significance of individual replicas requires recognizing and appreciating these specific linkages.

- The values that are given to replicas are complicated and risk being constrained by existing mechanisms. Replicas therefore invite alternative ways of thinking within institutional or disciplinary silos, as well as new ways of working within and across communities of interest.

- Institutions can help by making their replicas more accessible and visible, integrating them into their catalogues, database structures and their online searchability. The intellectual and practical benefits of cross-institutional, cross-sector thinking / action would extend well beyond replicas and any one country.

(C) Replicas merit the same care as other objects and places

- While allowing that some replicas continue to be used and made for educational and experimental purposes, replicas are ideally subject to the same evidence-based, research-led heritage / curatorial processes as other objects and places.

- Caring for replicas should therefore consider collecting, accessioning, recording, researching, designation, conserving, interpreting, presenting, deaccessioning and disposal, as appropriate.

- Significance assessment offers a framework for action based on transparent and holistic assessment of authenticity, value and significance of individual replicas and replica collections.

(D) Replicas invoke specific local and global ethical issues

- Replicas are and will continue to be an essential component of the world’s cultural heritage and strategies for its curation.

- Past practices or contexts of replica production may not have been, or may no longer be, deemed ethical. The consequences of such issues need to be identified and handled with due sensitivity and appropriate consultation.

- In creating replicas, contemporary ethical considerations include intellectual property, copyright and attribution, self-documentation of identity and integrity, the risk of physical impact on historic originals, and the positive and negative impact on communities of interest associated with the subject’s biography. The latter may be unexpected, hence the importance of an ethical review process that brings in multiple viewpoints.

- Contexts in which replicas are now being considered may already be highly contested, such as questions of restitution and repatriation, or relocation of historic originals because they are under threat in their current location.

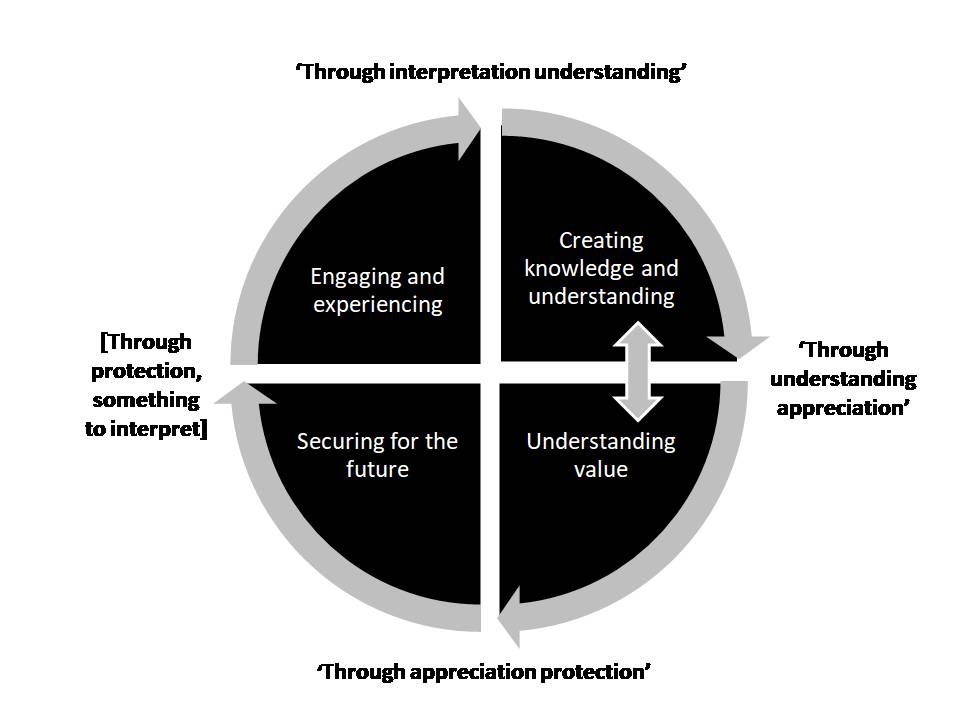

These cross-cutting principles underpin our guidance, which is divided into five areas. Sections 1–4 reflect a cycle in which an understanding of value, iteratively fed and shaped by knowledge and understanding, can be used to inform decisions about what to secure for the future, and how such resources can be engaged for wider public benefit, generating a desire to know more about the resource in question. Section 5 relates to creating new replicas.

Image: leaflet design Christina Unwin; image and graphic © Sally Foster