There is an emerging consensus that replicas of heritage objects and places can accrue a certain authenticity. But can replicas, somehow, extend the authenticity of the original object? Could they, even, be more authentic than the originals? Last month I gave a paper at ‘Futures’, the conference of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies, held as an online event at UCL. My paper, ‘Time and value at Bath Abbey: erosion, fragmentation and the role of the replica’ addressed the ways in which digital replication can create a deeper, or extended, sense of authenticity.

Bath Abbey is undergoing a major programme of restoration and conservation works called the Footprint Project, which includes repairs to (and in some cases the permanent removal of) the ledger stones which comprise the vast majority of the abbey floor. These ledger stones record through inscription the details of people buried beneath the floor; works in the 1860s, though, caused these stones to be rearranged so they no longer mark the direct location of those they memorialise.

My research has involved modelling those ledger stones which are most likely to undergo significant change during the project, creating a record of undesigned changes before these changes are redesigned or curated away. What these 3D representations capture is the authenticity of centuries of undesigned change at a moment in time – a moment in time that preserved a record of all moments in time that evidence themselves as interruptions upon surfaces. The replica, here anyway, is not intended to arrest the passage of time, but to acknowledge it. The replicas therefore make the biography – what Latour and Lowe (2011) termed the ‘trajectory’ – of selected stones more complete.

replication, especially of objects undergoing change, extend any understanding of the original and redefine our relationships with it

It is often asked whether the authenticity of an original object can somehow migrate to the replica. I suggest that replication, especially of objects undergoing change, extend any understanding of the original and redefine our relationships with it. Authenticity, I suggest, is an emergent and distributed property among a network of object, context, people and the representation. Rather than migration, which suggests a movement from one place to another, authenticity manifests itself more as a mumuration. It is fluid and dynamic.

My thinking has been much influenced by the work of Siân Jones and Sally Foster, and I was therefore deeply interested to learn of their July 2020 publication of New Futures for Replicas: principles and guidance for museums and heritage. This short document can be read as a manifesto for replicas. And as well as containing principles and guidance it poses some powerful and provocative questions, for example: What is it that the replica does that the historic original does not? What is the post-creation biography of the replica? What is the physical relationship to the historic original (such as accuracy and materials)?

I have further questions of my own. If we accept that no replica is a perfect copy, then what degree of accuracy is required? And just what is it that we’re replicating? Form? Mass? Narrative? Experience and wonder? Stuart Jeffrey warns that digital replication risks alienating audiences by foregrounding its ‘weirdness’ – that of a sanitised, remote and specialist medium. Jeffrey encourages a more creative and craft-based exploration of digital tools. He’s right. Digital replication ought not be limited to technocratic record-keeping; it can be a medium for interpretation and play, for changed perspectives, for emphasis and representational plenitude. The story of the original artefact can be re-presented and retold.

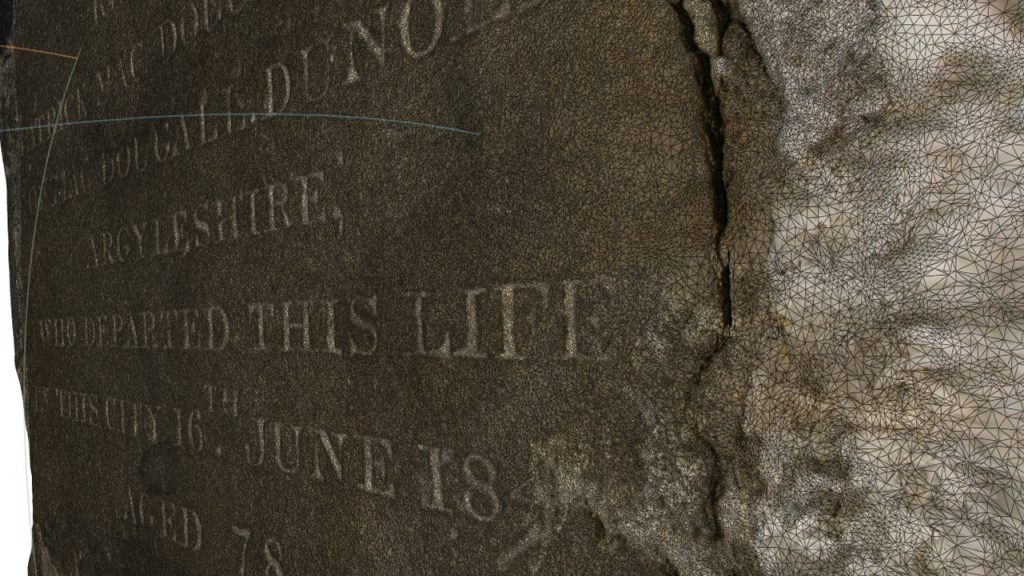

Bath Abbey’s ledger stone to Walter Borlase interests me. The stone, shown below, is replicated because it will change. It will be repaired, though the extent of repair is unclear.

The figure below, extracted from the replica, is not a true likeness. It is a selective representation of surface change, demonstrating that undesigned texture has become an integral part of the stone, that a two-dimensional surface is now quite hard to locate as inscription takes its place alongside a more complex (yet still authentic) topography – see: https://vimeo.com/455750724. It is this complex topography that is likely to be levelled during the repair process. The replica reveals, then, not just physical form but a situation and a value-set. Importantly, the replica also becomes the source material for the representation.*

Bruno Latour, defined agency as something that ‘modifies a state of affairs by making a difference’. Might the replica, and the representations derived from it, have agency? Can they make a difference? I suggest they can. Replicas can make a difference to the comprehension of the original as an authentic object. As tools for seeing and understanding, replicas surely develop a special authenticity all of their own.

As tools for seeing and understanding, replicas surely develop a special authenticity all of their own

* (In fact, almost perversely, the original might be seen as source material for the replica, much like the author’s manuscript is source for the novel. This is where art theory about the location of the ‘work’ becomes interesting – see Nelson Goodman, Richard Wollheim and Tim Ingold).

David Littlefield FRSA, Senior Lecturer: Design | Culture | Heritage | Place, Department of Architecture & the Built Environment, University of the West of England, Bristol

References and further reading

- Gallagher C and Greenblatt S (2001). Practising New Historicism. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Jeffrey S (2015). ‘Challenging Heritage Visualisation: beauty, aura and democratisation’. Open Archaeology, 1:1, 144-52.

- Latour B (2005). Reassembling the Social: an introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Latour B & Lowe A (2011). ‘The migration of the aura or how to explore the original through its fac similes’. In Bartscherer T (ed) Switching Codes, University of Chicago Press, 275-97.

- Morena J (2014). ‘Definitions of authenticity: a study of the relationship between the reproduction and original Gone With The Wind costumes at the Harry Ransom Center’. In Gordon R et al (eds) (2014). Authenticity and replication : the ‘real thing’ in art and conservation : proceedings of the international conference held at the University of Glasgow, 6-7 December 2012. Archetype Publications, 119-30.

- Sayes E (2014). ‘Actor–Network Theory and methodology: just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency?’. Social Studies of Science, 44:1, 134-49.

- Shanks M (2007). ‘Symmetrical Archaeology’. World Archaeology, 39:4, 589-96.

- Tilley C, Hamilton S, Bender B (2000). ‘Art and the re-presentation of the past’. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 6:1, 35-62.

- Waterton E & Watson S (2013). ‘Framing theory: towards a critical imagination in heritage studies’. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 19:6, 546-61.