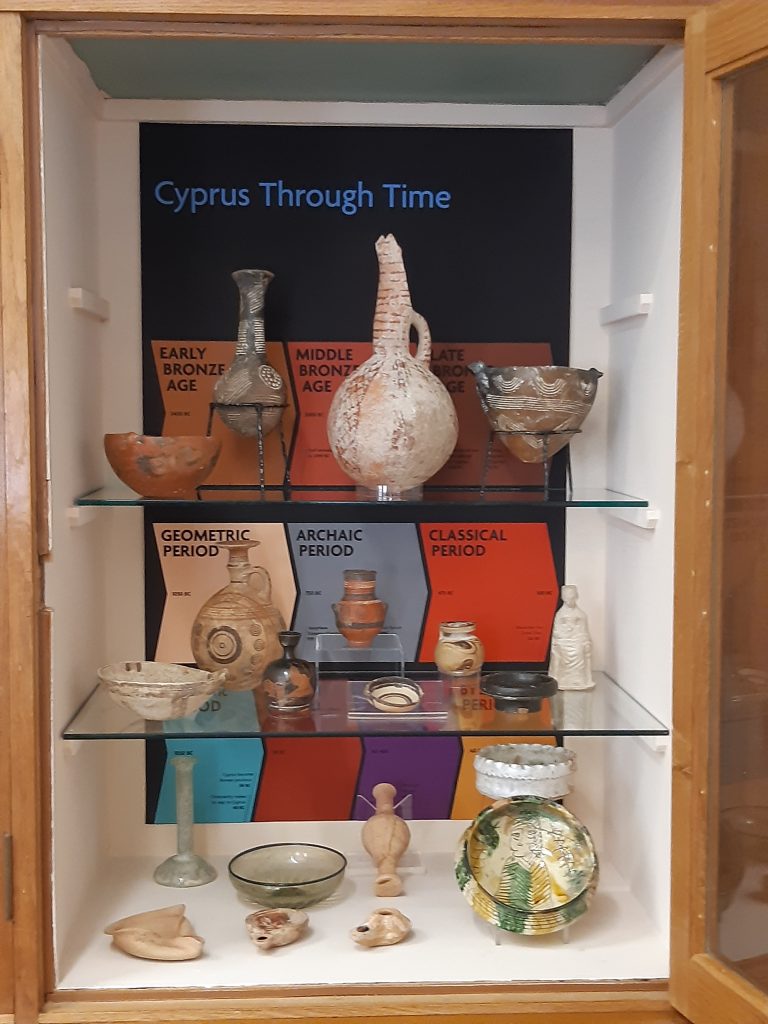

The Bridges Archaeology Collection

In 1994 Mrs Margaret Bridges, a Fife resident, donated a collection of Cypriot archaeological material to the University of St Andrews for educational use. The artefacts range in date from the Bronze Age to the Byzantine period and provide fascinating glimpses into the ancient world – from trade, technology and consumption to burial, beliefs and artistic expression. The collection is used extensively for hands-on teaching within the University’s School of Classics and the wider community, supporting skills development in creative writing, drama, art and digital literacy.

Research and engagement

From 2016-19, whilst working as Learning and Access Curator in the University’s Museum Collections, I collaborated with Professor Rebecca Sweetman (Head of School of Classics) on the ‘Through A Glass Darkly’ project, which sought to widen public access to the Bridges Archaeology Collection through digitisation and community programming. Our research aimed to establish whether 3D digital presentation changes perceptions of material culture. For example, might ‘virtual handling’ of an artefact help visitors grasp its original function, or deduce its history more easily than viewing it through a glass case? And what makes us categorise material in museums as ‘art’ or ‘archaeology’?

In order to answer these questions, 94 individuals of varied ages and archaeological experience were recruited to a focus group study, comparing four different interpretive formats: a traditional display case; a ‘sensory box’ containing ceramic replicas; 3D digital models, and handling of original artefacts.

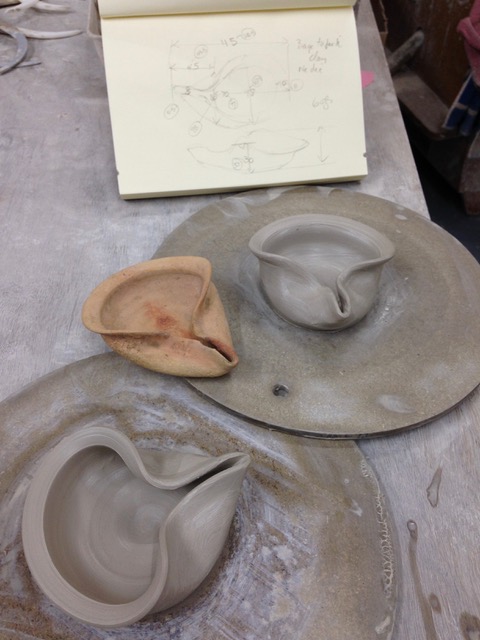

Replicas and experimental archaeology

To provide a realistic touch-only experience of archaeology, we approached a Fife ceramic artist, George Young (St Andrews Pottery), to create replicas of several artefacts: an Iron Age perfume bottle; a Hellenistic oil lamp; and a Bronze Age spindle whorl and jug. After sketching and measuring these artefacts in situ, George set about copying them in his studio. One benefit of working in clay, rather than 3D-printing, was that it provided fascinating insights into the original techniques used by the ancient Cypriot potters. For example, simple features like the central hole on the spindle whorl proved surprisingly difficult to imitate, whereas the pinched lamp could be produced in minutes on the wheel.

Audience research findings

During our focus group discussions, a number of recurrent themes emerged, including expectations of authenticity in museums and an assumption that objects displayed in cases had more artistic value. Attitudes to digital and physical replicas varied considerably:

- Digital replicas – Adults liked the visual quality and research potential but felt ‘distanced’ by the medium. Children were excited by the technology and used it more socially.

- Physical replicas –Adults were reticent at first, whereas children dived in. Archaeology and Anthropology students disliked the artificiality of replicas, being already accustomed to handling original artefacts. However, all groups focused more upon the materiality and possible function of the objects when exploring them through touch alone.

Overall, the multisensory nature of object handling was by far the most powerful experience, sparking personal associations and more considered interpretations. Subsequent experiments conducted with Dr Akira O’Connor (School of Psychology and Neuroscience) have shown that the heightened engagement with original artefacts also improves memory and learning. This is something I am now investigating as a doctoral student, in relation to museum programming for people living with dementia. There is a growing body of museological research indicating that participation in cultural activities improves health and wellbeing outcomes for people affected by dementia, but if museums are to fully exploit the power of their collections, further research is needed to evaluate the cognitive and wellbeing benefits of digital and physical experiences for this audience, and to understand the differences in using original and replica material.

Museums have always had to balance their commitments to access and preservation of collections, and replicas play an important role in this equation. Writing at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic has caused us all to reconsider attitudes to touch, proximity, the physical and the virtual, these questions seem more important than ever, demanding ever more creative solutions if museums are to continue offering meaningful and memorable, sensory experiences of heritage.

To find out more about our work, do visit our blog, Sketchfab pages or download a copy of our Quick Guide to creating 3D models, or feel free to get in touch!

Rebecca Sweetman, Professor of Ancient History and Archaeology, Head of School of Classics (University of St Andrews)

Alison Hadfield, Doctoral Student in Ancient History, Psychology and Information Studies (University of St Andrews and University of Glasgow), alh10@st-andrews.ac.uk

Further reading

- Camic, P.M., Kimmel, J. and Hulbert, S. (2017). Museum object handling: a health-promoting community-based activity for dementia care. Journal of Health Psychology 22, 1-12.

- Hindmarch, J., Terras, M., and Robson, S. (2019). On virtual auras: the cultural heritage object in the age of 3D digital reproduction. In: H. Lewi; W Smith; S Cooke; D vom Lehn (eds) (2019). The Routledge international Handbook of New Digital Practices in Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums and Heritage Sites. London: Routledge, pp. 243-256.

- Sweetman R and Hadfield, A. 2018. Artefact or art? Perceiving objects via object-viewing, object-handling, and virtual reality, UMAC Journal 10, pp.47-66.

- Sweetman, R., Hadfield, A., O’Connor, A. 2020. Material culture, museums and memory: experiments in visitor recall and memory, Journal of Visitor Studies, 23(1) pp.18-45.

- The Bridges Collection Project Blog.